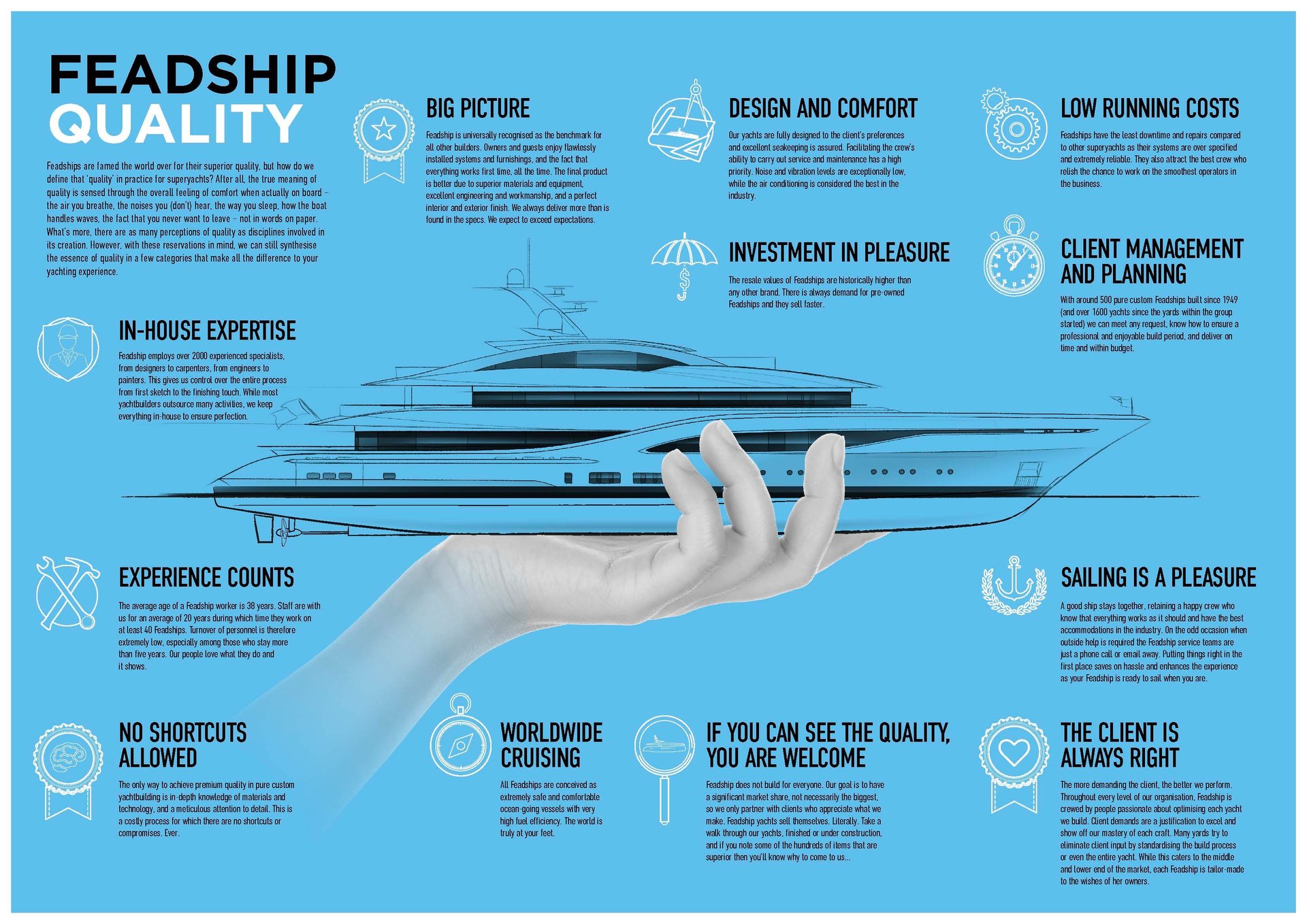

Perfection is important at Feadship; some might even call it an obsession. There is no perfection without quality, but what does quality mean exactly and how do we recognise good quality when we see it? Quantifying quality is essential if it is to rise above subjective opinion and be repeated in a reliable and consistent manner.

“For me, what I find interesting is how we achieve quality – the road, if you like, to perfection,” says Marc Levadou, Knowledge & Innovation Manager at Feadship. “Quality comes with hard work, experience and an eye for detail. It’s about who we are at Feadship, our shared heritage and our shared culture, and why that’s so important for the products we make.”

For yacht builders, delivering perfection requires understanding a client’s needs and seamlessly weaving his or her brief into the regulatory framework, and the engineering and production processes, to create a quality product. The best results come when you work together with passionate and knowledgeable people who really know what they're doing, but are also willing to push the boundaries to achieve the best outcome for the client.

“We build yachts that can be 100 metres or more in length and thousands of metres cubed in volume,” says Gillian Carter, Principal Project Manager at De Voogt Naval Architects. “That might not seem difficult, but there are so many pieces to the puzzle that make up these complex vessels and what's fascinating is when our engineering teams come together we’re always debating down to the last millimetre with the same objective in mind, which is to realise the client’s vision.”

For Ted McCumber, yacht captain and Managing Director of Feadship America, quality is “confidence in your vessel, knowing it was well designed, well-engineered, well-constructed, and knowing it can take you across the sea and arrive in one piece ready to take on guests. But it’s also the fit and finish, so when you open a door or a cabinet there's no noise or vibration. And sometimes Feadship might go too far; we had one client who complained his cabin was too quiet and we had to put in a fan unit so he had some background noise at night!”

Touchy Feely

Claude Roessiger is an entrepreneur and author who has made a careful study of quality in luxury markets and written a book on the subject, Perfection Matters. “Quality is design, function, finish and durability,” he says. “But how do you realise or recognise it? There are three standard measures of quality: it's what the eye sees, what the fingers touch, and the feel of a thing, which can be strangely defined as its ‘weight’. Light or heavy, it is the feel that tells you this is quality. So what is quality? It's in the perception of the person seeing it, touching it, feeling it.”

Among leading brands, the concept of quality is entwined with their corporate culture. Philosophically and emotionally satisfying, once the notion of quality becomes a valued commodity in a company it can be communicated to inspire passion in others.

At that point it no longer relies on individuals but is part of a wider culture that takes in the entire workforce, as well as trusted suppliers and subcontractors.

“An eye for detail is in our veins and there is this intrinsic need of many people at Feadship to make things look good,” says Pier Posthuma de Boer, Feadship Director of Refit & Services. “What’s striking about our culture and is, is that we're basically a collection of very old family businesses, and I think the fact that we've been around for so long has a decisive impact because it creates a sense of belonging. We're all very proud to work at Feadship and we have the feeling we're contributing to something bigger.”

Tradition vs innovation

While researching his book, Roessiger was curious to know if there was a common thread that linked high-quality brands and the organisations behind them. What he discovered was that they all innovate continuously and develop new concepts, but at the same time value their history and heritage.

For Feadship, innovation and tradition go hand in hand. The list of Feadship firsts is too numerous to mention, but one in particular highlights how innovation in the past continues to inform the present. Frits de Voogt, who penned scores of yachts between 1960 and his retirement in 1995/92, recalls LAC II, the first yacht in 1975 to have a roll-out helipad. It would not be long before this unique innovation was on the wish list of other prospective owners and helipads are now virtually de rigeur on superyachts. It is no coincidence that the Feadship Heritage Fleet was set up in 2013 as an association for owners of registered Feadships of over thirty years old in recognition of their contribution to the brand’s rise to global prominence. Scrupulously maintained by their owners, these yachts still enjoy cruising the world in style and comfort as testimony to their quality standards of construction.

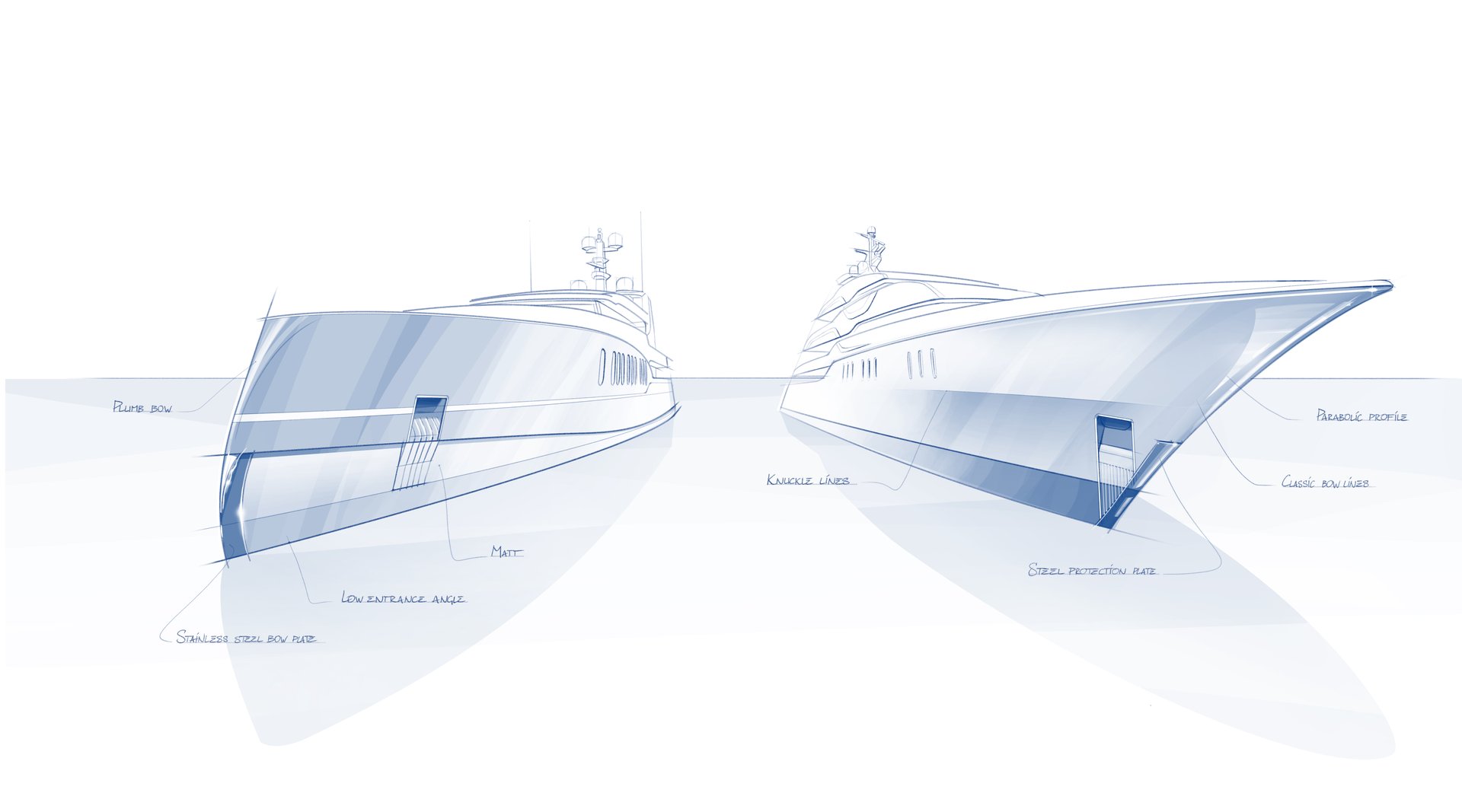

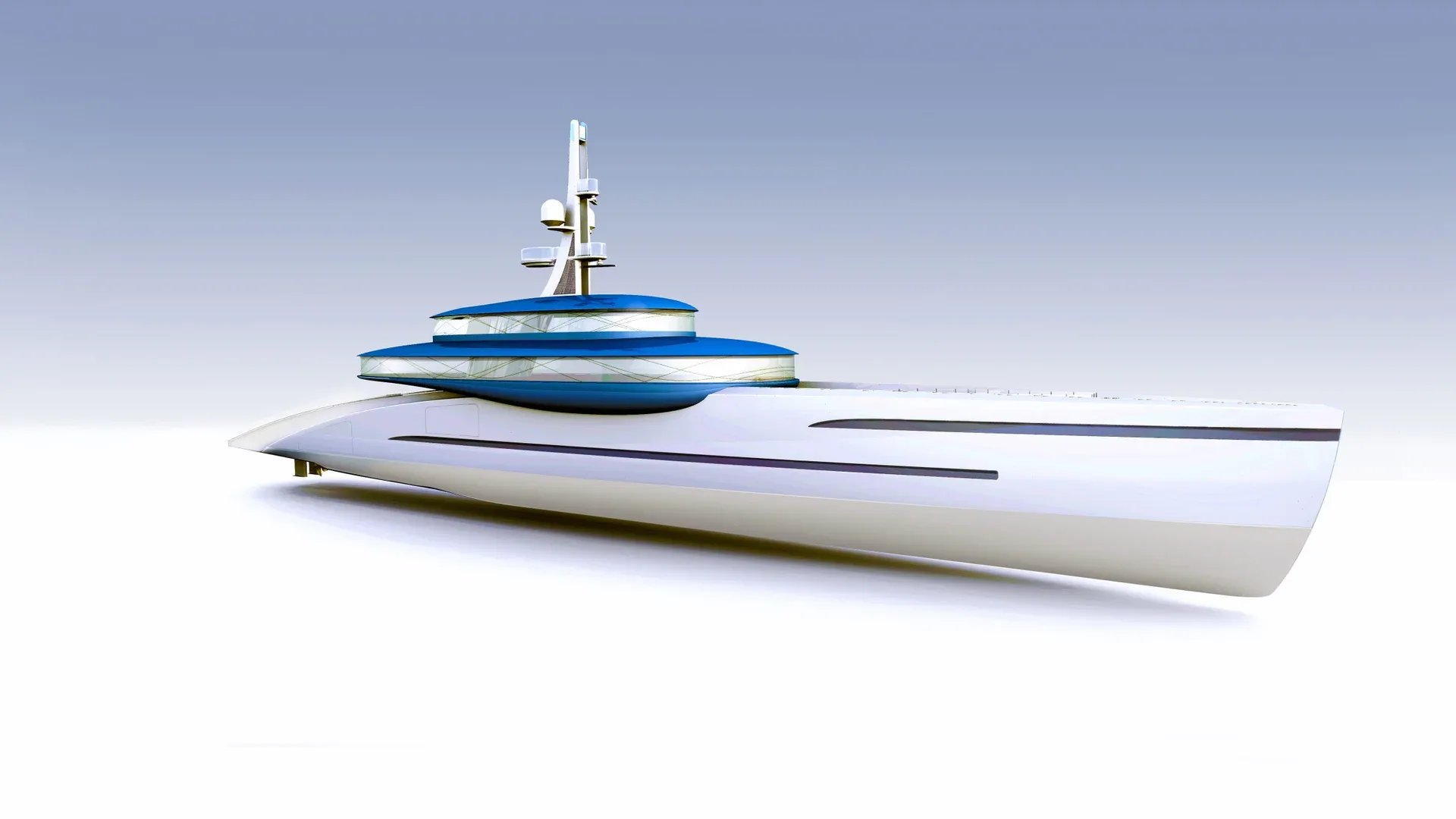

For the engineers and naval architects, digital technologies such as FEM (Finite Element Analysis) and CFD (Computational Fluid Dynamics) are now indispensable tools in the pursuit of perfection. By digitally recreating the stresses and strains on a yacht in specific sea conditions, factors such as hull strength, shape, stability and performance can be accurately defined before cutting metal. Onboard systems are now completely engineered in 3D and the same technology is being utilised within the production environment. Feadship uses Microsoft Hololens, an untethered holographic VR device that engineers can wear when on board in-build projects to simulate the piping and cable runs, for example, to make sure everything fits in the allotted space and avoid subsequent reworking.

“What we are doing today was simply not possible when engineering in 2D,” says Kai Britzek, Project Management Engineering. “Using live 3D models allows us to make best use of the entire space and we’re only limited by what is technically possible. Everyone is working at the same time, and we can see how changes affect the other disciplines. The model shows how it should all fit, but sometimes it only becomes apparent in production how to solve certain challenges.”

Feadship has formulated its own comfort index, an algorithm that calculates the baseline comfort level owners should be able to experience onboard. It has even developed a computer code for estimating how pool water behaves in certain seaways to prevent sloshing and built a test tank to compare the predicted and real-life results. The interesting next step is validating the data created in the engineering phase with onboard sensors that measure forces and performance in real-time operation.

“Before my department was started, we used to do the R&D within the project itself,” says Marc Levadou. “Now we do it beforehand so there is less risk when we start building. But we also follow up by collating and analysing data during the operation of the yacht and work backwards to further perfect our design processes and construction techniques.”

The Miracle Room

At the end of the day, Feadship’s function is to turn dreams into reality. This can be a subjective process open to interpretation, which makes it all the more important that it is properly managed. “Of course, we work with our own team but also with suppliers, sub-contractors and co-creators,” explains Marsha van Buitenen, Feadship Sales Director. “That’s a big group of people, so we have to have a lot of processes in place to manage them and the owner’s expectations.”

Key to this management process is the concurrent design system, a methodology that takes an integrated approach to product development by gathering department specialists together with the owner’s team so decisions can be taken concurrently to resolve issues or concerns during the design process. Utilised across numerous industries and especially the aerospace sector, Feadship developed its own method in conjunction with the European Space Agency (ESA).

“What does a space rocket or satellite and a Feadship have in common?” asks Michel Wit, Feadship Quality & Concurrent Design Coordinator. “They are custom designs that must be functional and reliable in harsh conditions, which is why we went to the European Space Research and Technology Centre in Noordwijk here in the Netherlands for advice when we sent up our own system in what we call the Miracle Room. The essence is to bring all the stakeholders together and my role is to facilitate the group and guide them seamlessly through the entire design process.”

“Quality is also about trying to keep things simple,” warns Jan-Bart Verkuyl, Feadship Director. “You can easily over-complicate the yacht, but it still has to be maintained, it still needs to float, it still needs to function. And so one of my missions is to put common sense on the table and ask ‘Is this really needed and what is the added value?’ But as long as we approach yacht building with the same philosophy we’ve aways had, Feadships will continue to evolve and stand the test of time.”