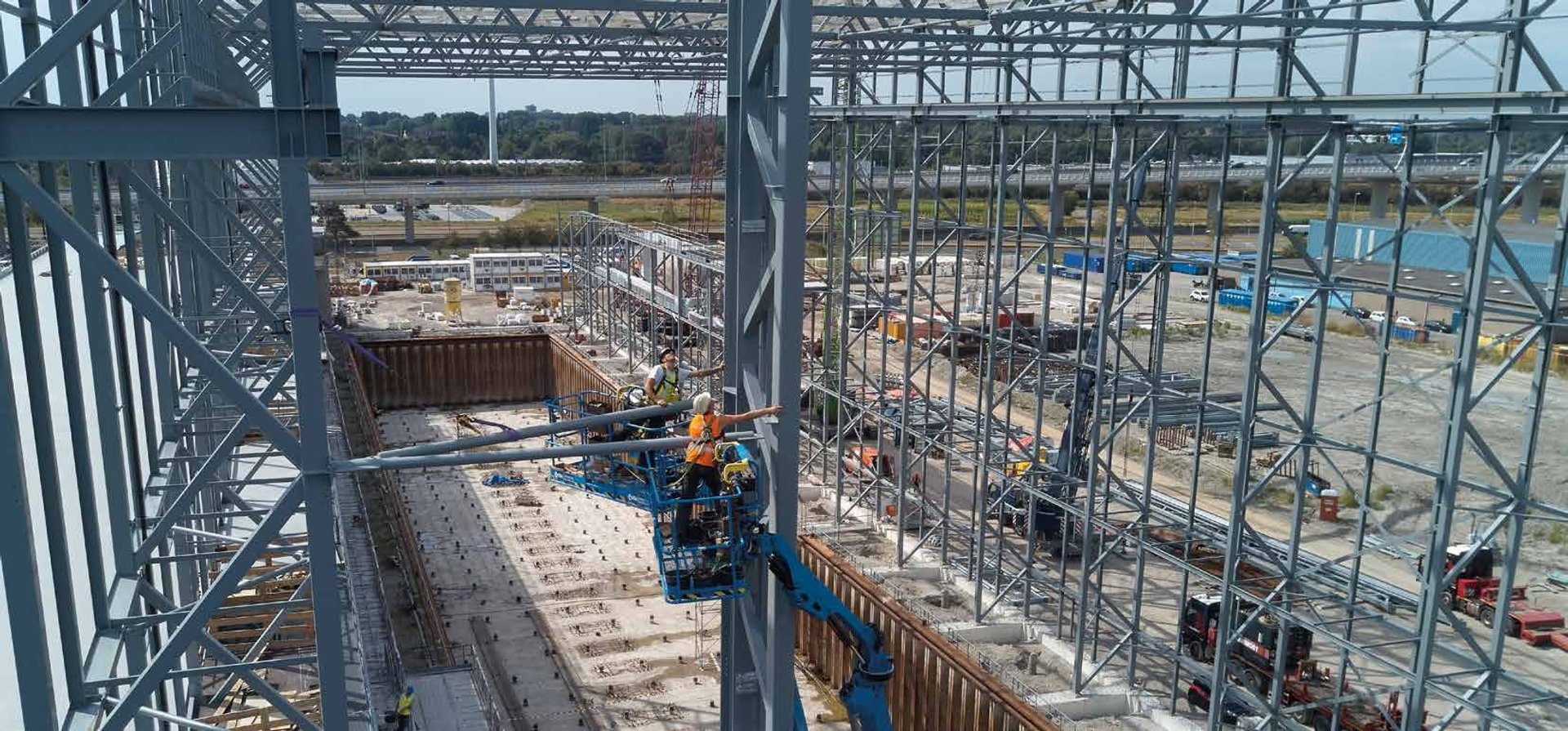

Five years, a team of four main contractors, seventeen consulting firms, 59 key suppliers, two construction management firms and thousands upon thousands of hours of planning went into making Feadship’s new Amsterdam yard a reality. This is not a facility that takes the name ‘state-of-theart’ lightly. The 425,000 m3 yard has been completely streamlined from (under-) ground up in order to offer unprecedented quality and speed. Overhead cranes that run 50% faster. Frequency-controlled hoisting equipment that allows for greater precision. Solar panels on the highrise roof and LED lighting for eco-friendly construction. Feadship’s fourth shipyard is the pinnacle of contemporary design. Come take a look inside.

Having spent much of 2014 looking at various possible sites for the fourth Feadship facility, Peter van Mil, operational director at the yard on Kaag, had one more viewing to make. The fact that it took just 20 minutes to reach the location in Amsterdam was an immediate plus-point as the new yard would need to work in tandem with the Kaag yard, and proximity would be a big help. Stepping out of his car on a pleasant autumn afternoon, surveying the impressive space available, Peter could imagine a bespoke construction hall in this spot. Another advantage was the wide water lapping at the quay shore: knowing this meant that new and refitted Feadships would have easy tidal access to the sea, Peter smiled. The search was over. Almost five years later, a state-of-the-art superyacht facility has added a modern new highlight to Amsterdam’s venerable skyline. The project made the most of Feadship’s unrivalled understanding of the techniques and logistics involved in creating complex structures. And there were other synergies with Feadship’s core business of building world-class yachts, too.

The new facility required many months of meticulous planning, design work and engineering calculations before construction could get underway. It also involved a carefully calibrated partnership with many different expert parties and disciplines. Peter ultimately found himself leading a team of four contractors (civil engineering, steel construction & building frame, technical installation and infrastructure), seventeen consultants (including for architecture, climate systems, fire prevention and building safety), 59 key suppliers and two construction management firms.

The result is an ultra-modern complex that is the most sustainable superyacht building location in the world. It’s all a far cry from the very first family yard linked to Royal Van Lent, opened in 1849. And we can safely say that the generations of boatbuilders who played their part in this evolving 170-year history would never have envisaged superyachts of well over 100 metres in length being built by Royal Van Lent at the heart of the Dutch capital. Nor could they have imagined a grand opening ceremony involving over 2500 people, including some truly distinguished guests. But to set the record straight for future generations, here are a few of the other milestones in the creation of this outstanding new Feadship complex, a pinnacle of modern design and technology…

Pile driver power

The site of the new yard is three metres below sea level, with the groundwater table ever-present just beneath the soil surface. The construction process therefore started with driving piling sheets for the dry dock and the foundation piles to support the buildings. A total of 1049 piles were placed: 359 vibro-combi piles in the dock and 690 vibro piles for the aboveground construction. The dock piles were put in place using the largest pile driver equipment available in the Netherlands.

Underwater action

Divers had to prepare the tips of the vibro-combi piles by removing the grout layer around them. After cleaning the sheet pile walls and adding a gravel layer to stabilise the dock floor and catch sludge, they placed reinforcement cages around the piles. This was physically demanding work, with visibility in the murky water often no more than five centimetres: much of the time the divers simply had to feel their way around with their hands. Each spent 1.5 hours at a time underwater welding, drilling and sanding, supported by two people on dry land: one in charge of steering and coordination and a stand-by diver ready to jump in and help in case of trouble. Once the divers had prepared everything, it was time to pour the underwater concrete – 3900 mÑ, or almost 9000 tonnes of it – in a single phase which took 64 uninterrupted hours. The crew worked day and night in shifts to deal with no fewer than 300 truck deliveries.

In on the ground floor

The underwater concrete floor was thoroughly cleaned and prepared for the building of the construction dock floor. Some 4000 holes were drilled in the underwater concrete to anchor the reinforcement steel of the construction floor, after which the reinforcement wires with a diameter of twenty millimetres were fitted one by one. The ultimate count was an unprecedented 275 kg/mÑ of reinforcement per cubic metre of concrete – but then, the construction floor will need to support the finest yachts in the world during their build.

The heights of independence

Construction on the complex advanced to the point where it achieved its maximum height of 35 metres at noon on 4 July 2018. In accordance with building industry tradition, the milestone was marked by a flag-raising ceremony. Port of Amsterdam supported the event by sending a fireboat which sprayed ‘holy water’ over the harbour in a spectacular show.

Nerves of steel

The steel assembly of the low-rise part of the complex involved a series of intricate operations on components small and large. A 750-tonne Mammoet crane was used to fit several beams and columns, each of which weighed 8400 kg and measured 13.5 metres in length and six metres in width. The precast concrete slabs were also put in place at this time.

On the edge

The edge of the new dock was probably the most discussed element of the design phase for the new yard. What’s so special about a humble piece of masonry? Based on a mock-up and built with mobile sheet pile walls, the dock edge was carefully designed to allow electricity, compressed air and industrial gases to be brought across the entrance bridges to the jetty and yachts, freeing up the airspace above for building work and giving the construction hall a much more streamlined look. It wouldn’t be Feadship if it wasn’t brilliant.

Seen from above

The construction hall has three V-type overhead cranes with a span of 36.65 metres and a capacity of 2 × 12.5 tonnes each. Open-truss beams make the cranes lighter than standard versions, exerting less pressure on the building structure. They’re also 50% faster, offering major savings over time. Frequencycontrolled hoisting motors allow for perfect precision – a key issue given each crane can lift 25 tonnes. The two hoists on each crane can be used individually or in fiftytonne tandem, synchronising the hoist rpms and safety circuits. The size of the cranes meant they had to be fitted in the short time window available between completing the hall walls and placing the roof: this was achieved using two mobile 250-tonne hoisting cranes.

Hot concrete

Pouring the concrete for the third floor of the building at a height of 17 metres would have been a challenge at any time: doing so on a day when temperatures reached 32 degrees Celcius was a very delicate operation. Concrete that hardens too quickly can form small cracks so the choice was made to add Delft Green Intermezzo – a 100% biodegradable substance based on alginates extracted from seaweed – to the wet concrete, where it could form a layer and slow down evaporation. A type of concrete especially suited to the heavy reinforcement was used.

Open and shut case

The twenty-tonne shipyard door was assembled in the port of Amsterdam and transported to the site with a floating crane. Despite its thirtyby- thirty-metre span, installation took only a few hours. Comprised of a horizontal truss framework and super-strong polyester canvas, the door opens/closes via synchronised heavy-duty electric winch motors. When opening, the lower beam helps pull the trusses above it upwards, while the canvas neatly folds either side of the framework like an accordion. Every aspect of this elegant solution from strength calculations, wind stress computations and production to transport, assembly and installation was engineered to a t.

In the dock

The dock door was brought to the Feadship site using the floating heavy lift crane, as well as a floating pontoon an tugboats. Getting this huge element into place was an exploit in its own right, with no more than 140 millimetres of wiggle room on either side. The moment the door was fully in place was heralded by the blowing of three air horns.

Mission accomplished

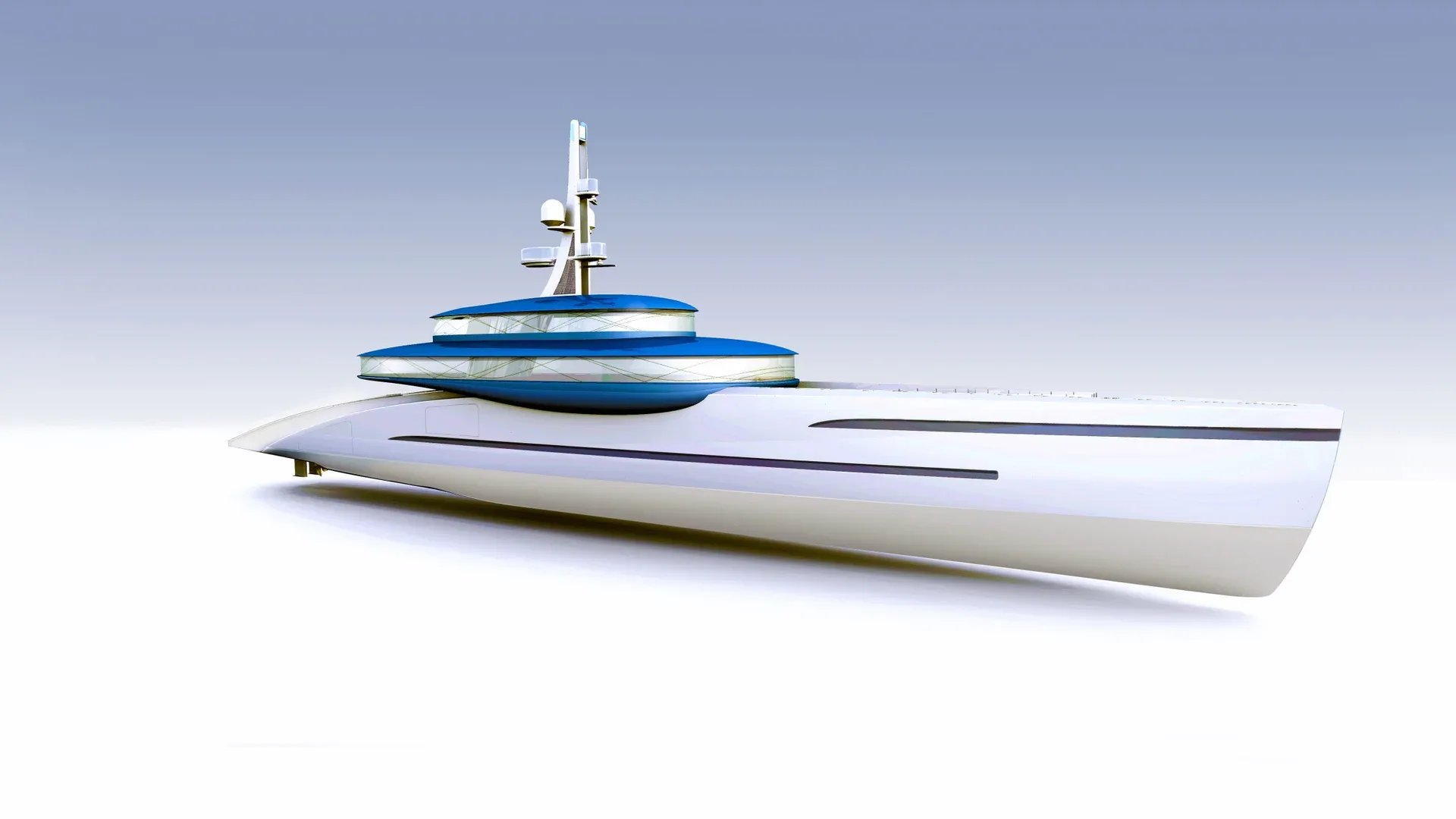

As soon as the construction hall was completed it welcomed the hull of the first new-build project. An 88-metre masterpiece in her own right, #816 will also go down in history as the very first Feadship to be launched in Amsterdam.