Regulations are all around us. And although they have a bad reputation (it’s a hassle, limits freedom, gets you fined, adds cost, et cetera et cetera) there are good reasons for their existence. Those reasons are usually “for your own good”, like safety for yourself and others, a level playing field between competitors and protection of public resources like the planet we share.

Even in a small sector like yacht building, it’s easy to get lost in this forest of rules, laws, guidelines, standards, notices, circulars and their relations to each other. In this whitepaper we’ll try to show the various levels and grades of general maritime and yacht-specific regulations, their applicability and effects on design and levels of interpretation. Two things need to be said before we go on:

- This whitepaper is incomplete. There’s always more if you look deeper.

- Notwithstanding your creative solutions for any written requirement, never forget that the laws of nature are not up for interpretation.

Structured regulations

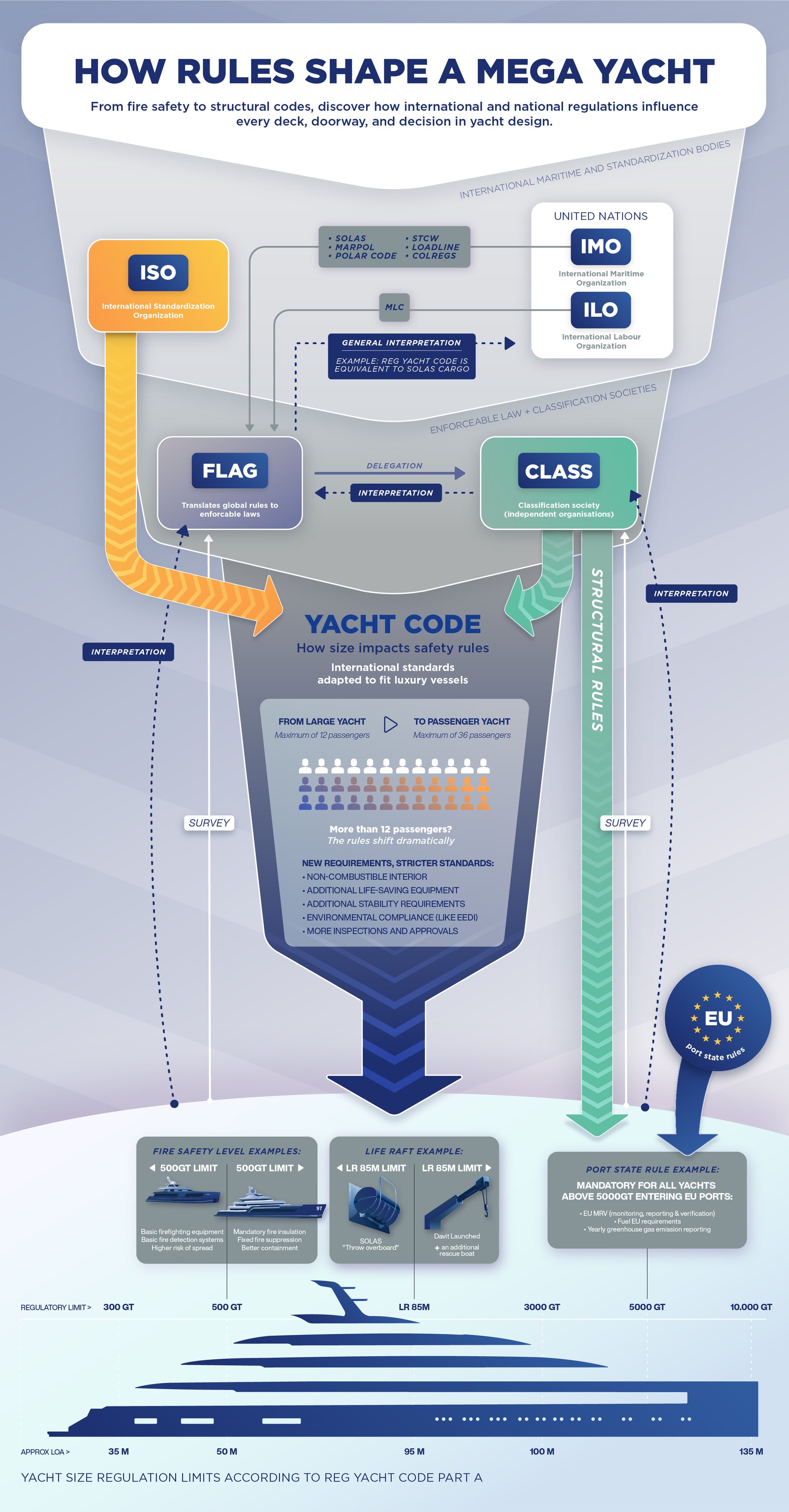

Regulations exist on various levels: International, National and Classification being the major ones. To start with the International ones, usually recognisable by the “I” in their acronyms: IMO, ILO and ISO. These three, the International Maritime/Labour/Standardisation Organisations, create regulations on a worldwide level, in order to level that playing field and define and/or raise standards. Well known terms in our industry are SOLAS, MarPol, Polar Code, STCW, Loadline and ColRegs (by the IMO), MLC (by the ILO) and the ISO standard on glazed opening (11336). These regulations are usually developed after large accidents (SOLAS was developed after the Titanic sinking), long-term abuse or malpractice (MLC was developed after decades of crew abuse and little enforcement of old ILO conventions) or the push for improvement (MarPol developed and continuously updated to clean up our oceans). Although there are no final conclusions it is expected that the sinking of sailing yacht Bayesian in 2024, the most serious yacht casualty in the past decades, will have repercussions in regulations.

However, international entities like the IMO/ILO/ISO cannot enforce their regulations. There is no such thing as an international police force or quality control to keep all parties in line. This is where national regulations (also known as “flag” regulations) come into play. By translating the international conventions into national law, flags are able to confirm compliance with that law (e.g. by issuing the certificate of registration) which will make the process of convincing the Port State Control surveyor (of another country) that the yacht actually complies a lot easier. Within these national laws the text of international regulations can either be fully integrated (which also gives some room for interpretation), or referenced (which keeps it automatically updated if the international standard changes).

Classification Societies, like LR, BV, DNV, RINA, ABS, are independent organisations, originating in the early insurers; before the rise of the international conventions like SOLAS, if you wanted your ship and cargo insured, you had to comply with their requirements. Nowadays, Class Rules and guidelines have a significant overlap with Flag rules, since they use the same international conventions as a basis for their rules. The main contribution to the regulatory landscape is the structural Class rules, which define the dimensions of all structural components in very high detail. Since that is missing in the international conventions, flags usually refer directly to class for this aspect. Class also provides for a lot of optional notations, like UMS (unmanned machinery space), ECO (environmental protection), ICE (operation in sea ice), Winterisation (operation in cold air), Cyber (digital safety), UWN (underwater noise) et cetera. NB: mentioned notations are from Lloyd’s, different classification society will name these differently.

The EU is an international body but, unlike IMO, not worldwide so takes up an intermediate spot. EU regulations however are often implicitly adopted by member states, so can be a factor of influence since the EU often favours regulations instead of leaving it to the market. In yachting the EU RCD (recreational craft directive) is a major instrument for yachts below 24m. The EU has not (yet) created specific rules for the large yacht sector.

The EU tends to be ambitious in the sustainability area, which can be seen in the EU taking the IMO Hong Kong convention (recycling of ships, 2009) and adopting it in EU law before the convention was adopted and entered into force internationally. This regulation is the reason yachts need to carry an IHM (inventory of hazardous materials) when they enter a EU port. Similarly The EU developed the EU MRV (Monitoring, Reporting and Verification) and FuelEU in parallel to the IMO DCS (Data Collection System). These regulations require ships above 5000GT (including yachts!) to yearly report their greenhouse gas emissions when visiting European ports. Yachts under 5000GT do not have to comply with these regulations, but as offshore ships between 400 and 5000GT have been added to the regulations by 2025, it is expected that yachts will soon follow.

Specific Yacht Codes

The main flags of the yachting sector (Red Ensign Group, Marshall Islands, Malta) each have developed yacht-specific rulebooks based on the international regulations. Since they have the same source, these regulations are similar, but due to different structuring and some freedom of interpretation, they are not fully identical. SYBAss, the SuperYacht Builders Association, is pushing flags for a unified yacht code, which would make it easier to change flag or to build under different flags and would put a stop on cherry-picking or “flag-shopping” for the most lenient interpretations.

Probably the most well-known regulation is the Red Ensign Group Yacht Code (Part A and Part B, formerly known as the Large Yacht Code and Passenger Yacht Code). This code was originally developed in the nineties, when yacht were getting larger, and were being actively chartered, and thus ended up having to comply with SOLAS but not being built accordingly. Now in its fifth generation, the REG Yacht Code is used by many yacht builders as their de facto standard, with strong industry participation in the updating and development of the code.

Part A provides an equivalent level of safety to a SOLAS cargo vessel. Since a SOLAS cargo vessel may have a maximum of 12 passengers on board, this is well suited for the majority of the yachting fleet. When a yacht accommodates more than 12 passengers (up to 36) it needs to have an equivalent level of safety to a SOLAS Passenger vessel, which is the basis of Part B. There is some leniency though: most flags will allow a maximum of 36 passengers on a Part A compliant yacht, with case-by-case restrictions in sailing area and period, as long as it is not operating commercially at the time (chartering).

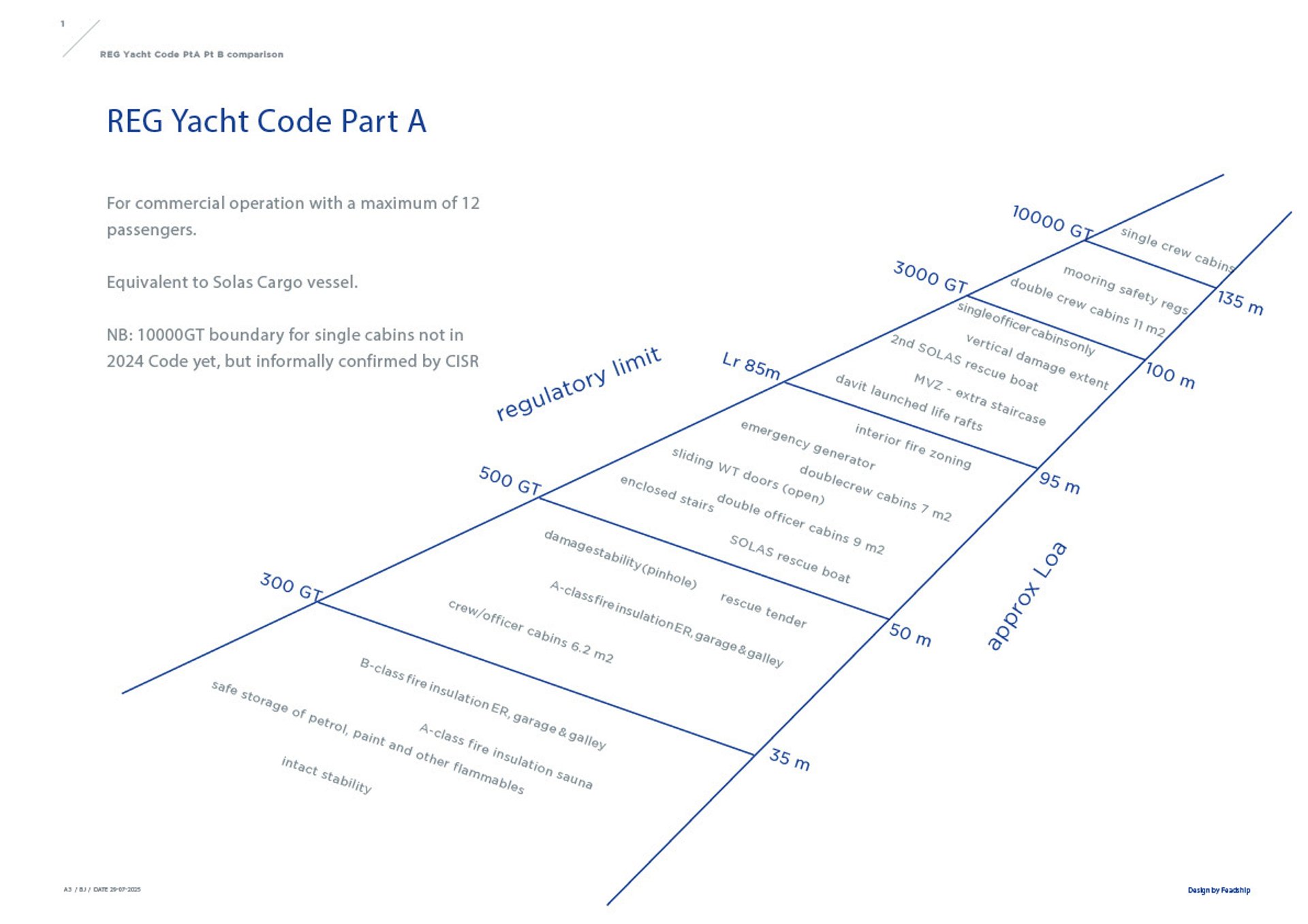

Within the REG Yacht Code there are several boundaries which come from international conventions and which have a significant effect on the design, build or operation of the yacht. The main ones are 400GT (MarPol), 500GT (SOLAS), 1500GT(STCW), 85m (SOLAS) and 3000GT (MLC). If a design crosses one of these boundaries, additional requirements come into play. This is the reason there are so many yachts of 499GT: from 500GT onwards, you have to fit those pesky features making the yacht much more safe, like extensive fire insulation and fire extinguishing systems, an emergency generator, sliding watertight doors and an approved rescue boat installation. In the figure below the various boundaries are shown with the main effects on design and equipment.

Figure 1 REG Yacht Code Part A (structure)

All yacht codes contain similar requirements on areas like stability, fire, life saving appliances, nav/com equipment, crew accommodation, machinery and electrical systems. Each time one of the limits is exceeded, the safety level goes up and at the same time design effort goes up, cost goes up and design freedom goes down. As an example, when the limit of 85m Loadline length (one of the many different defined lengths of a yacht) passes 85m, the requirements for damage stability change from pinpoint damage (each watertight compartment, however small, is assumed damaged independently) to damage extent (a virtual block of damage is applied to the yacht, damaging all compartments in the envelope). This means more attention has to be paid to the watertight subdivision of the yacht, with the end result it will be more resilient to damage than the smaller vessel. At the same time, the “throw overboard” life rafts are exchanged for davit launched life rafts (so-called “dry-shod evacuation”) and an additional rescue boat is to be fitted. These are large items which have to be accommodated in the early design stages, and add weight and cost to the yacht, but again, when necessary (which we all hope will be never) they will make the evacuation safer.

Fire is one of the worst things to happen on a yacht at sea. We’ve all seen the pictures in the media of yachts burnt to the waterline, and sinking either due to fire damage or to external extinguishing efforts. Luckily no personal casualties have occurred in these fires, but material damage is sufficient to catch the eyes of flag states and insurers. The most serious fires occur in the fleet below 500GT. Fires do happen in the larger yachts, but they tend to be contained within spaces due to the required higher fire insulation and compulsory fixed fire extinguishing systems (e.g. watermist system). The Red Ensign Group code is currently incentivising the fitting of fixed fire extinguishing systems by allowing Short Range yachts to grow from 300 to up to 500GT if one of those systems is fitted.

Interpretations and alternative design

With the rampant creativity which the yachting sector is famous for, it often happens there is a clash with regulations. This is where interpretation comes into play. An interpretation is an agreement valid for a single yacht design between class or flag surveyor and the designer/builder. The aim is always to provide the same level of safety which would be the result of directly following the prescriptive regulations, but in a different manner. Other interpretations occur when a situation rises for which no regulations exist. For instance, the use of sliding glass panels to create a wintergarden creates a space which could be seen as exterior space but also as interior space, which would result in different and contradicting requirements. As a result, interpretations were developed for these projects, but since they came up so often these interpretations have now been included in the REG Yacht Code (14B.23 Covered Category (9) (Open Deck) Spaces).

When the difference to the prescriptive regulations is too large, the SOLAS “Alternative Design and Arrangements” procedure can be followed. This procedure uses risk based design to find, assess and mitigate risks associated with any designs which are highly innovative and do not fit in common regulations. AD&A uses multidisciplinary sessions called HAZID and HAZOP (Hazard identification and hazard operability), where experts on all aspects of the design cooperate to list all possible risks and the ways to reduce or avoid them. AD&A is used in yacht building to assess novel fuel features, Feadship has used this for the liquid hydrogen fuel cell system on board “Breakthrough” and the methanol storage systems on various Feadships in build.

Industry involvement in development of regulations

To ensure regulations are fit for purpose, it is important that the industry is involved in their development. As a matter of fact, one of the reasons that SYBAss was founded was the lack of participation of the yachting sector during the development of the MLC, the Maritime Labour Convention. When the MLC was published in 2006 is was soon clear that the requirements were disastrous when applied to yachts, which in time led to the development of yacht-specific interpretations of MLC being integrated in LY3 by the REG in conjunction with an industry working group. SYBAss is now a recognised NGO (non-governmental organisation) within the IMO structure, and not only follows development of international rules for awareness of the yachting industry, but also plays an active role to ensure rules being developed take effects on yachts and yachting into consideration.

Furthermore, yachting companies can individually join the participation at various points. Feadship is one of the active contributors at many levels of regulatory developments, due to the belief that well considered regulation will improve the industry without creating too many barriers to creative design. Apart from regular contacts for individual projects, Feadship participates in the following regulatory working groups, to advise on improvements, give feedback on safety or compliance issues and get the opportunity to review upcoming regulations:

- REG Yacht Code industry working group (since 2009)

- Lloyd’s Yacht Technical Advisory Committee (since startup 2017)

- ISO working groups on paint, glass, sustainability and other Large Yacht standards (since 2010)

- Marshall Islands Yacht Code consultation phase (2025)

- SYBAss technical Committee, GHG working group (since startup 2015)

- Dutch national standardisation committee Yacht Building (since 2018)

Conclusion

The application of a professional set of regulations creates additional value on an already high value asset like a yacht. The regulations ensure a minimum level of safety, a good basis for comparison between competitive products and assure all lessons learned in the past are applied on a new design. Although impact on design is evident, there is still sufficient room for creativity. Feadship, as a full custom yacht designer and builder, is happy to support the development of fit-for-purpose regulations for the yachting world.