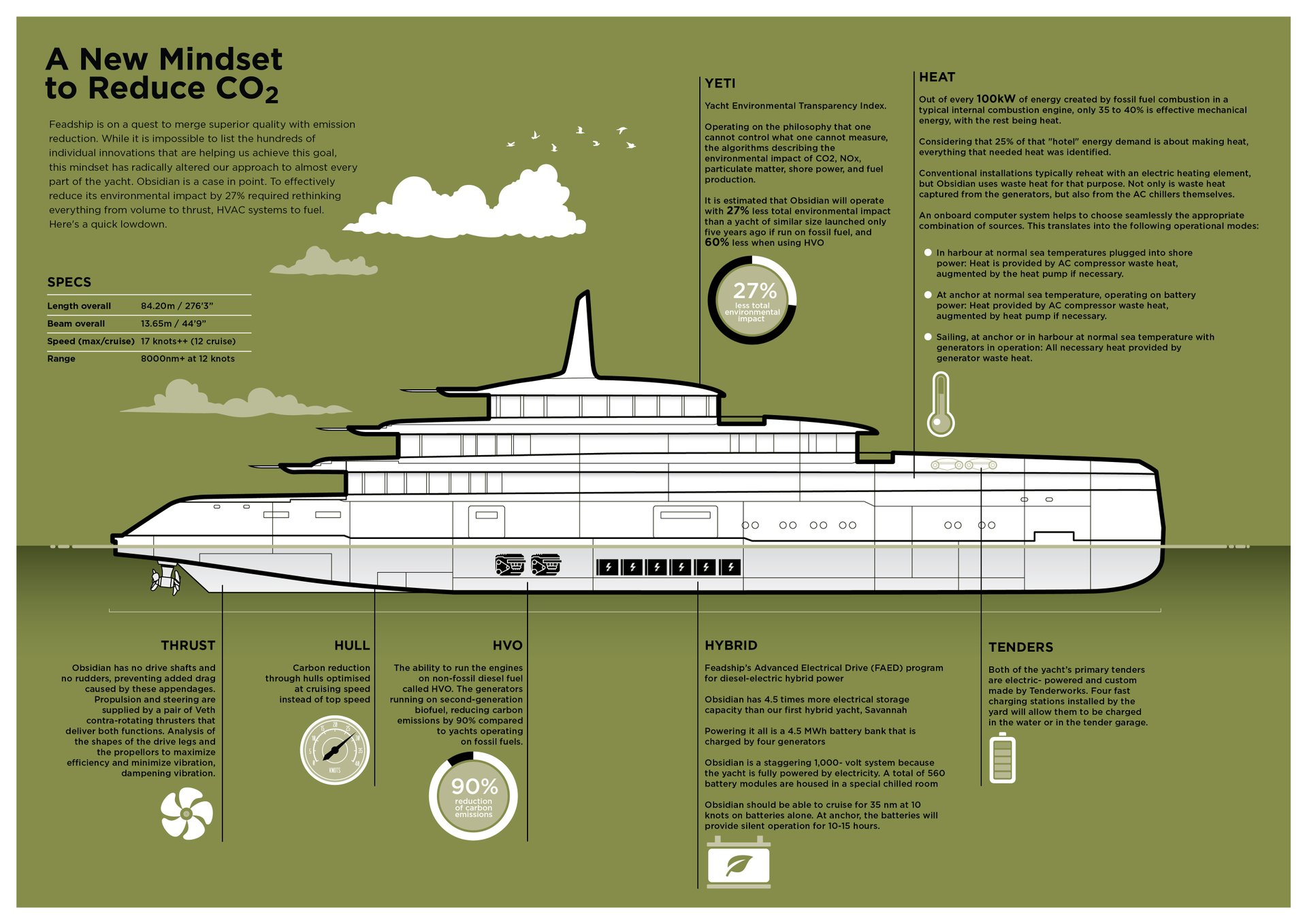

Since unveiling its ground-breaking hybrid Savannah back in 2015, Feadship has been on an outspoken mission to produce carbon-neutral superyachts by 2030. In fact, the specific brief for the 84.20-metre Obsidian was to be more energy efficient and emit less carbon than Savannah. As a result, Obsidian is the first of a new generation of large yachts that are consciously constructed to reduce carbon emissions through optimising hulls at cruising speed instead of top speed, weight control, advancements in electric propulsion and the ability to run engines on Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil (HVO), or non-fossil diesel biofuel that emit 90% less carbon than fossil fuels. Obsidian should be able to cruise for 35 nm at 10 knots on batteries alone. At anchor, the batteries will provide silent operation for 10-15 hours.

Transparency

What differentiates Obsidian from all its predecessors is that, next to reducing carbon emissions, it addresses its overall environmental impact. The emissions of nitric oxide and nitrogen dioxide (NOx), particulate matter, hydrocarbons and the impact of building materials like steel, aluminium, fairing compounds, antifouling, teak, interior finishing, and more, were all scrutinized during the design process and calculated using life cycle assessments (LCA) and the Yacht Environmental Transparency Index (YETI), a sustainability index developed by Bram Jongepier, Senior Designer at Feadship De Voogt Naval Architects. YETI revealed how all a yacht’s components and operations contribute to its carbon profile and environmental impact.

Operating on the philosophy that one cannot control what one cannot measure, the algorithms describing the environmental impact of CO2, NOx, particulate matter, shore power and fuel production have been made freely available by Feadship to the signatories of the Water Revolution Foundation, a yachting industry association dedicated to driving sustainability in the superyacht industry through collaboration and innovation. This led to a Joint Industry Project (JIP) under the flag of the Water Revolution Foundation with twenty major partners in the yachting industry. The YETI JIP produced a tool which, with data augmented now by other partners like engine manufacturers, predicts the environmental impact of a standardized operational year in the yacht’s lifecycle. Jongepier estimates that YETI effectively captures 90 per cent of the total lifecycle of a yacht and each new build helps gather more data.

“Using this tool, we calculated that Obsidian operates with 27 per cent less total environmental impact than a yacht of similar size launched only five years ago if run on fossil fuel, and 60 per cent less when using HVO,” he says.

Diesel-electric hybrid power

Building on innovation from Savannah and using Feadship’s Advanced Electrical Drive (FAED) program for diesel-electric hybrid power, Obsidian has 4.5 times more electrical storage capacity than Feadship’s award-winning hybrid yacht from 2015. She has no drive shafts or rudders, preventing added drag caused by these appendages; propulsion and steering are supplied by a pair of Veth contra-rotating thrusters that deliver both functions. Veth’s experience with compact units for ships operating on rivers was seen as a perfect fit for a yacht specified for a relatively shallow draft. Feadship and Veth collaborated on computational fluid dynamics (CFD) analysis of the shapes of the drive legs and the propellors to maximize efficiency and minimize vibration, dampening vibration being another key component of the brief.

Powering it all is a 4.5 MWh battery bank that is charged by four generators — two large and two small, custom, variable speed units based on tweaked CatC32 engines with permanent magnet alternators that deliver power as needed. Where Savannah and Lonian (2018) operated on 560 volts, the DC system on Obsidian is a staggering 1,000-volt system because the yacht is fully powered by electricity. A total of 560 battery modules are housed in a special chilled room amidships on the tank deck, revealing another benefit of the hybrid system: the components no longer need to be adjacent. The thrusters are in the best location for steering and water flow, while the generators and their exhaust systems, batteries and electrical switchboard are located elsewhere for optimal weight distribution and crew access. Obsidian can cruise for 35 nm at 10 knots on batteries alone and, at anchor, provide silent operation for 10-15 hours.

Carbon-free energy

From the outset, Feadship understood that advanced propulsion alone would not result in the level of fuel savings required to meet Obsidian’s goals. However, when analysing Obsidian using the YETI tool, they learned that 60 per cent of the energy consumed goes to powering the onboard lifestyle like air conditioning, heating, hot water, lighting, cooking, entertainment electronics, pools and laundry service. The team therefore set out to reduce the energy needed to provide for the yacht’s ‘hotel’, developing innovations like peak load shaving and reducing HVAC demand through the computerized management of cooling guest and crew zones. They also focused on capturing ‘waste’ heat. Out of every 100kW of energy created by fossil fuel combustion in a typical internal combustion engine, only 35 to 40 per cent is effective mechanical energy, with the rest being heat, usually discarded overboard with the water-cooling system and in the exhaust gasses. Feadship’s design and engineering team responded with a much more comprehensive system than using generator cooling water to heat a swimming pool, a process that has since become standard for many superyacht builders.

Next up was rethinking the air conditioning, which is typically the largest producer of waste heat, the reason being that to sufficiently dehumidify the surrounding sea air, the HVAC system needs to cool incoming fresh air to about 7 degrees Celsius. However, to keep the interior from feeling like a meat locker, heating units must then warm the air to the desired temperature for each room. Conventional installations typically reheat with an electric heating element, but Obsidian uses waste heat instead, captured from both generators and the AC chillers themselves. This is not just free energy, but essentially carbon-free energy because it reuses incidental heat generated by another function.

“There are so many points of energy savings integrated on this yacht that it is hard to count,” said Project Manager Mark Jansen.

Urged to explore all avenues of reduction, Feadship also introduced an innovative heat pump system to pull heat from other sources, including ambient sea water. This thermal energy transporting heat pump used in Obsidian is five times more efficient than making heat with a regular electrical heating coil, according to Jongepier.

An onboard computer system helps to choose seamlessly the appropriate combination of heat sources. In harbour or at anchor at normal sea temperatures, whether plugged in or operating on battery power, heat is provided by AC compressor waste heat and augmented by the heat pump if necessary. When using generators, heat is provided by generator waste heat.

Form follows function

To further reduce its ecological footprint, De Voogt’s naval architects created a low, slim hull, optimized at cruising speed using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) with the final form being made into a model tested in a towing tank. Complex engineering for balance and weight reduction includes new applications for carbon fibre. The louvered aft deck overhangs, for example, are all carbon fibre attached to the aluminium superstructure and require no support pillars. This weight benefit also offered new deck layout possibilities.

For the first time in many years, Feadship has delivered a yacht with a single level engine room, which gave her designers considerably more freedom in creating the interior layout. It also lends more space for guest accommodation and features a total of seven staterooms. According to Jansen, the volume of this 84-metre yacht is typical of that on 100-metre Feadships.

The layout is just as bold and modern as the exterior profile would suggest. Both the exterior styling and interior design are by the British firm RWD, in collaboration with MONK Design. There are surprising destination spaces such as an asymmetrical atrium staircase leading to a lower deck dining saloon with an entire wall that opens to provide a terrace view just 75cm above sea level.

Near the stern is an Aqua Lounge where massive windows below water level offer a unique view from the nearby gym. The Aqua Lounge can also function as a cinema and even a classroom.

From decks to the interior, the design leitmotif is all about surprise – most of the corridors and many of the rooms, as well as all of the al fresco living spaces, are not oriented on a fore and aft or athwartships axis. In fact, except for staterooms, none of the interior rooms have any 90-degree angles. A hidden staircase to a study and a sunken lounge on the main deck are just two more of the unexpected interior elements. But the biggest surprise involves the use of submarine anchors. Eliminating the need for a mooring deck forward allows Obsidian to feature a fantastic interior bow observation lounge with double curved glass floor-to-ceiling windows. Access is via a main deck corridor from the guest accommodation area through the tender garage to this hidden gem.

In keeping with the carbon reduction theme, both of the yacht’s primary tenders are electric- powered and custom made by Tenderworks. Four fast charging stations installed by the yard allow them to be charged in the water or in the tender garage.

23 Years in the Making

The idea behind Obsidian’s diesel electric system didn’t happen overnight; in fact, it dates back to 2000, the year Feadship began offering a range of diesel electric propulsion solutions for new builds. Long used on cruise ships and other marine applications, Feadship saw considerable promise in modifying diesel electric propulsion to the specific needs of superyachts where the demand for power varies enormously between sailing and lying in a harbor and the significant difference in power requirements between maximum speed and cruising speed.

Feadship was eager to bring the benefits accrued from diesel electric propulsion to its yachts, including reduced noise and vibration, especially at low speeds, improved maneuverability, especially at ultra-low speeds, and the possibility of installing azipods, which save onboard space. Other advantages of diesel electric propulsion include smaller components, providing greater freedom when designing the yacht as a whole. Similarly, the reduced size of the exhausts opens up a wider range of options for the layout of the engine room.

Ultimately, Feadship saw the potential of diesel electric propulsion as an environmentally friendly system. Because the engines run less often at low capacity, pollution is reduced, the overall energy consumption is more efficient, and less fuel is required. Finally, there are gains in terms of redundancy.

It took four years to design and build Obsidian, but its diesel election propulsion was 23 years in the making.